4 Scientific realism

Can we claim to know anything about reality? Is it a goal of science to describe reality? Does science make any progress at describing reality? This outline focuses on the issues of metaphysical progress from science, while the Outline on the scientific method discusses the epistemological foundations and limitations of science.

This could have been called the outline of “Metaphysics” or “The realism debate”.

4.1 Metaphysics

4.1.1 Introduction

When one encounters the word “metaphysics”, what is usually meant is one of the three following ideas:

- What really exists, or at least what exist literally beyond what we know in physics. This is one of the oldest and fundamental branches in philosophy. In a naturalist sense, high-energy theoretical physics can be seen as examples of theoretical metaphysics at its best, ideas about about what there exists at a more fundamental level based on what we know at more pedestrian levels of experience.

- A pejorative word, denoting ideas that are meaningless because they are claims beyond what is verifiable. This was the view of the positivistists.

- A loosely, if ill-defined, woo-woo word in which a mystic, guru, or metaphysician may claim to specialize.

Russell:

[T]he attempt to conceive the world as a whole by means of thought.

van Inwagen:

The word ‘metaphysics’ is derived from a collective title of the fourteen books by Aristotle that we currently think of as making up Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Aristotle himself did not know the word. (He had four names for the branch of philosophy that is the subject-matter of Metaphysics: ‘first philosophy’, ‘first science’, ‘wisdom’, and ‘theology’.) At least one hundred years after Aristotle’s death, an editor of his works (in all probability, Andronicus of Rhodes) titled those fourteen books “Ta meta ta phusika”—“the after the physicals” or “the ones after the physical ones”—the “physical ones” being the books contained in what we now call Aristotle’s Physics. The title was probably meant to warn students of Aristotle’s philosophy that they should attempt Metaphysics only after they had mastered “the physical ones”, the books about nature or the natural world. 1

1 van Inwagen (2014).

Stealing from encyclopedia.com:

In medieval and modern philosophy “metaphysics” has also been taken to mean the study of things transcending nature—that is, existing separately from nature and having more intrinsic reality and value than the things of nature—giving meta a philosophical meaning it did not have in classical Greek.

Especially since Immanuel Kant metaphysics has often meant a priori speculation on questions that cannot be answered by scientific observation and experiment. Popularly, “metaphysics” has meant anything abstruse and highly theoretical—a common eighteenth-century usage illustrated by David Hume’s occasional use of metaphysical to mean “excessively subtle”. The term has also been popularly associated with the spiritual, the religious, and even the occult. In modern philosophical usage metaphysics refers generally to the field of philosophy dealing with questions about the kinds of things there are and their modes of being. Its subject matter includes the concepts of existence, thing, property, event; the distinctions between particulars and universals, individuals and classes; the nature of relations, change, causation; and the nature of mind, matter, space, and time.

- Quine, W.V.O. (1948). On what there is. 2

- Ney, A. (2014). Metaphysics: An introduction. 3

- Bryant, A.K. (2017). What’s metaphysics all about? 4

- Williamson, T. (2020). What is metaphysics?

4.1.2 Conceptual distinctions

4.1.3 Criticism

- Positivism

- Ladyman, J. & Ross, D. (2007). Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalised. 5

5 Ladyman, Ross, Spurrett, & Collier (2007).

See also:

4.2 Realism and antirealism

4.2.1 Introduction

- Naive realism

- Why would I doubt that the world I see is real?

- Reification fallacy

- Phenomenal conservatism

4.2.2 Ancient skepticism

- Plato

- Meno’s paradox

- Plato’s Apology

- Plato’s Cratylus - On the correctness of names

- Plato’s Republic - Allegory of the Cave 6

- Pyrrhonism

- Sextus Empiricus (c. 160-210 CE)

- Agrippa’s trilemma

6 Plato, Republic VII 514–520, Cooper & Hutchinson (1997), p. 1132–7.

Aquinas on truth:

Moreover, that there is truth is self-evident, because whoever denies that there is truth concedes that there is truth, for if there is no truth, then it is true that there is no truth. But if something is true, then it follows that there is truth. 7

7 Summa Theologiae, Part One.

4.2.3 Early modern skepticism

- Many philosophers in that Early Modern Period had threads of Idealism (wikipedia: reality itself is incorporeal or experiential at its core). e.g. George Berkeley, Kant, Friedrich Hegel, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

- Descartes’ demon

4.2.4 Modern skepticism

9 Wittgenstein (1969).

Korzybski:

A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness. 10

10 Korzybski (1933), p. 58.

Borges:

On Exactitude in Science

… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

—Suárez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lérida, 1658 11

11 Borges (1998), p. 325.

Schrödinger quoting Schopenhauer:

The world extended in space and time is but our representation. 12

12 Schrödinger quoting Schopenhauer in “Mind and Matter”.

- TODO: There’s a lot more to antirealism than skepticism about the external world.

4.2.5 Contemporary skepticism

- Contemporary skepticism 13

- Khlentzos, D. (2011). Challenges to metaphysical realism. SEP. 14

- Putnam Brain in a vat 15

- Chalmers, D. (2003). The Matrix as metaphysics. 16

- Bostrom - The Simulation Argument

- Am I a more advanced civilization’s tamagotchi?

- Distinguish Anti-realism from non-realism

Radiohead:

Just ’cause you feel it, doesn’t mean it’s there. 17

17 Radiohead. (2003). Song: “There There” on the album Hail to the Thief.

See also:

4.3 Humeanism and necessity

4.3.1 Necessitary connections

- Hume’s doctrine of no necessitary connections.

- Emphasize the naturalist revolution within Humean views.

Criticism:

- McRobert, J. (2002). Mary Shepherd’s two senses of necessary connection. 18

18 McRobert (2002).

See also:

4.3.2 Laws of nature

4.3.3 Humean supervenience

- Donald Davidson

- David Lewis on Humean supervenience:

4.4 Idealism

4.4.1 Introduction

- TODO

4.4.2 History

- Gorgias (483-375 BCE)

- Jakob Böhme (1575-1624)

- George Berkeley (1685-1753)

- K.L. Reinhold (1757-1823)

- Johann Fichte (1762-1814)

- Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation (1792)

- Georg Hegel (1770-1831)

- Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854)

- T.H. Green (1836-1882)

- F.H. Bradley (1846-1924)

- Josiah Royce (1855-1916)

- J.M.E. McTaggart (1866-1925)

- McTaggart, J.E. (1908). The unreality of time. 23

- Benedetto Croce (1866-1952)

- Giovanni Gentile (1875-1944)

23 McTaggart (1908).

See also:

4.4.3 Criticism

- Mary Shepherd (1777-1847)

- Atherton, M. (1996). Lady Mary shepherd’s case against George Berkeley. 24

- Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

- Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872)

- Analytic philosophy

- Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

- George Edward Moore (1873-1958)

- Roman Ingarden (1893-1970)

- Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970)

24 Atherton (1996).

See also:

4.4.4 Discussion

- Guyer, P. & Horstmann, R.P. (2023). Idealism in Modern Philosophy. 25

- Solipsism

- Markus Gabriel equates German idealism with realism (3 mins)

25 Guyer & Horstmann (2023).

4.5 Instrumentalism

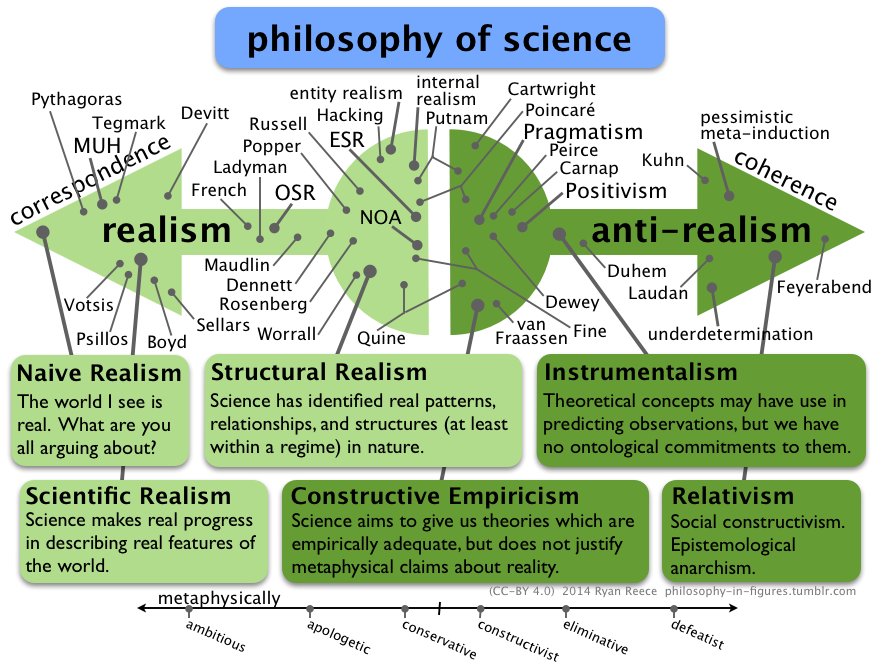

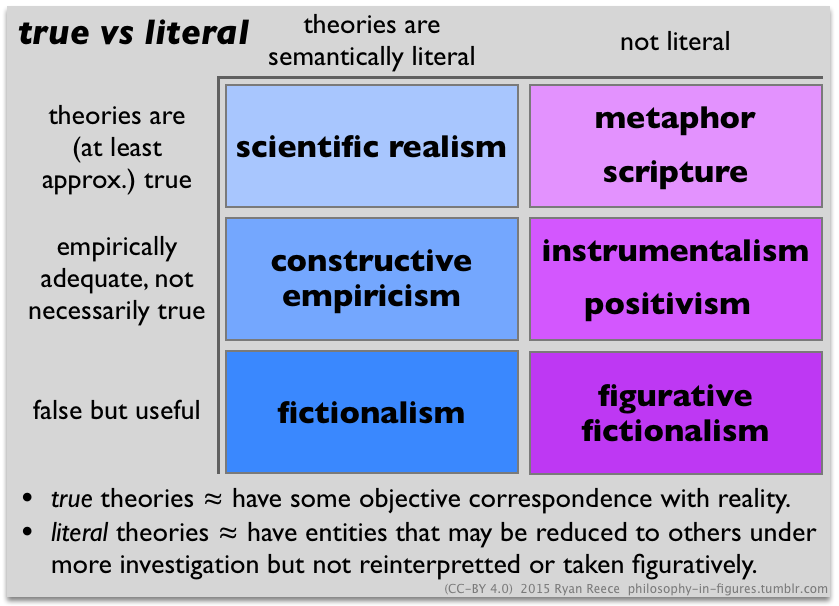

With realism and antirealism being one of the oldest dichotomies of positions in philosophy, a way of classifying the tension in more recent philosophy is between instrumentalism and scientific realism, each with many varieties. First let’s look at instrumentalism.

4.5.1 First pass

Theoretical concepts may have use in predicting observations, but we have no ontological commitments to them.

- Antirealist

See also:

4.5.2 History

- Pierre Duhem (1861-1916)

- Percy Williams Bridgman (1882-1961)

- Bridgman, P.W. (1927). The Logic of Modern Physics.

- operationalism: coining the term operational definition

- Bridgman, P.W. (1927). The Logic of Modern Physics.

- Later Wittgenstein in PI. See Postpositivism, below.

26 Torretti (1999), p. 242–243.

4.5.3 Discussion

- Barrett 27

27 Barrett (2004).

Redhead:

There is an enormous gap between so-called analytic philosophy which broadly agrees that there is something special about science and scientific method, and tries to pin down exactly what it is, and the modern continental tradition which is deeply suspicious of science and its claims to truth and certainty, and generally espouses a cultural relativism that derives from Nietzsche and goes all the way to the postmodern extremes of Derrida and his ilk. There is also the social constructivism that sees scientific facts as mere ‘social constructions’ and is a direct offshoot of the continental relativism. But the analytic tradition itself divides sharply between instrumentalism and realism, the former seeing theories in physics as mathematical ‘black boxes’ linking empirical input with empirical output, while the latter seeks to go behind the purely observational data, and reveal something at least of the hidden ‘theoretical’ processes that lie behind and explain the observational regularities. 28

28 Redhead (1999), p. 34.

4.6 Scientific realism

4.6.1 First pass

Some attempts at definitions:

Science makes real progress in describing real features of the world.

Chakravartty:

To a very rough, first approximation, realism is the view that our best scientific theories correctly describe both observable and unobservable parts of the world. 29

29 Chakravartty (2007).

Chakravartty:

Scientific realism is a positive epistemic attitude towards the content of our best theories and models, recommending belief in both observable and unobservable aspects of the world described by the sciences. 30

30 Chakravartty (2017). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-realism/

- Helmholtz

- Boyd

- Sellars

- Chakravartty

- Psillos, S. (1999). Scientific Realism: How science tracks truth. 31

- Sankey

31 Psillos (1999).

Helmholtz:

What Helmholtz then asserted, in his classic essay “On the Facts of Perception,” is that the inference to a hypostasized reality lying behind the appearances goes beyond what is warranted by the lawfulness obtaining among appearances. Indeed, all localizations of objects in space are really nothing more than the discovery of the lawfulness of the connections obtaining among our motions and our perceptions. The difference between what is genuinely perceived and its realistic interpretation is just the difference between the regularities in our perceptions and the hypothesis of enduring, substantial sources of the perceived regularities (Helmholtz 1977, 138–140). 32

32 Oberdan, T. (2013). Moritz Schlick, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Sankey:

Correspondence theories which treat truth as a relation between language and reality are the only theories of truth compatible with realism. 33

33 Sankey (2001), p. 37.

The realist aim for science is to discover the truth, or the approximate truth, or the truth with some associated degree of error, about not only the observable aspects of the world but also its unobservable aspects. Associated with this is the elimination of error, or its minimization, while truth is maximized. While the pursuit of science may increase our ability to control the environment, or to predict observable phenomena, these are secondary pursuits compared with the realist’s aim of acquiring (approximately) true theories. 34

34 Nola & Sankey (2007), p. 338.

4.6.2 Challenges to scientific realism

The primary dichotomy of positions is between forms of scientific realism and instrumentalism.

- Khlentzos, D. (2011). Challenges to metaphysical realism. SEP. 35

- Wray, K.B. (2018). Resisting Scientific Realism. 36

- The problem of induction. See also: The problem of induction

- Instrumentalism

- Positivism; linguistic frameworks; principle of tolerance; verificationism

- Underdetermination

- Language dependence; Duhem-Quine thesis; the problem of translation; theory ladenness

- Scientific revolution

- Normal science and revolutionary science; paradigm shift - Kuhn

- Pessimistic meta-induction - Laudan

- Social constructivism

- The lore of our forefathers - Quine

- Research traditions - Laudan

- Epistemological anarchism - Feyerabend

- TODO

- TODO: work through the challenges presented in these videos.

- And this, this, and this.

- TODO: move some of this discussion to the next sections on instrumentalism and postpositivism.

See also:

- Superseded theories in science

- Discussion of the Science Wars in Criticisms of naturalism in the Outline on naturalism

4.6.3 Superseded theories in science

Poincaré:

At first blush it seems to us that the theories last only a day and that ruins upon ruins accumulate. Today the theories are born, tomorrow they are the fashion, the day after tomorrow they are classic, the fourth day they are superannuated, and the fifth they are forgotten. 37

37 Poincaré (1913), p. 351.

- Aristotelian physics

- Ptolemaic solar system

- Phlogiston theory

- Élan vital

- Herring, E. (2023). Thinking with élan: A supremely stylish critic of scientific overreach.

- Newtonian gravity

- Galilean relativity

Also:

- Superseded theories in science - wikipedia

- relationship to pessimistic meta-induction

4.6.4 Realist rebutals

- Note that some “superseded theories” are the correct theory at some coarse-grained or renormalized scale or regime, e.g. Newtonian gravity is the correct low-energy limiting theory of general relativity. See: Newtonian gravity.

- See also the discussion of effective field theory.

- Frost-Arnold, G. (2020). One way to test scientific realism. Obscure and Confused Ideas (blog).

- Park, S. (2021). Embracing Scientific Realism. 38

- Optimistic Induction

38 Park (2021).

Coleman:

Rovelli:

Our arguments have to be about the world we experience, not about a world made of paper. 40

40 Rovelli (2003), p. 5.

Schumm:

There is a difference, however, between working crossword puzzles and the pursuit of higher mathematics. In the case of mathematics, you don’t triumph over the capricious machinations of another human being (the designer of the puzzle) but, rather, over the absolute fabric of logical relations. The body of knowledge you have developed has the enviable characteristic of being demonstrably and absolutely true, given the set of assumptions (axioms) underlying your contemplations, irrespective of the foibles of your own human limitations, indeed, irrespective of the existence of humanity itself. And, as an added bonus, if it should so happen that the set of axioms on which your intellectual fortress is built is somehow relevant to the physical world, then you can even walk away with a deeper understanding of your natural surroundings. The wonder of group theory is that its relevance to the disciplines of both mathematics and natural science far exceeds the self-contained boundaries within which it was first developed. 41

41 Schumm (2004), p. 144.

4.6.5 No miracles argument

There are older forms of the argument, but Putnam’s first phrasing that magnified the discussion, when he claims that

realism is the only philosophy that doesn’t make the success of science a miracle. 42

42 Putnam (1975a), p. 73.

- No Miracles Argument (NMA)

- Prediction with science works

- Inference from success to truth

- Putnam

- Boyd

- Discovery of Neptune

- Discovery of Higgs boson

- Reliabilist epistemology

4.6.6 Scientific progress

- The growth of knowledge 43

- Chu, J.S. & Evans, J.A. (2021). Slowed canonical progress in large fields of science. 44

See also:

- Progress in the Outline on Naturalism

- Scientific knowledge in the Outline on the Scientific Method

4.7 Positivism

4.7.1 Introduction

- antirealist

- nominalism

Positivism is a philosophy of science and epistemology that roughly defends a qualified empiricism, that the scientific method is the only route to knowledge, and that all statements that cannot be empirically verified are meaningless. Positivism is strongly eliminative about metaphysics and claims that many metaphysical questions and positions are not open or false, but meaningless because of their lack of attachment to empirically demonstrable things or effects.

Google:

Logical positivism: a form of positivism, developed by members of the Vienna Circle, that considers that the only meaningful philosophical problems are those that can be solved by logical analysis.

Chakravartty:

According to the best known, traditional form of instrumentalism, terms for unobservables have no meaning all by themselves; construed literally, statements involving them are not even candidates for truth or falsity (cf. a more recent proposal in Rowbottom 2011). The most influential advocates of this view were the logical empiricists (or logical positivists), including Carnap and Hempel, famously associated with the Vienna Circle group of philosophers and scientists as well as important contributors elsewhere. In order to rationalize the ubiquitous use of terms which might otherwise be taken to refer to unobservables in scientific discourse, they adopted a non-literal semantics according to which these terms acquire meaning by being associated with terms for observables (for example, “electron” might mean “white streak in a cloud chamber”), or with demonstrable laboratory procedures (a view called “operationalism”). Insuperable difficulties with this semantics led ultimately (in large measure) to the demise of logical empiricism and the growth of realism. The contrast here is not merely in semantics and epistemology: a number of logical empiricists also held the neo-Kantian view that ontological questions “external” to the frameworks for knowledge represented by theories are also meaningless (the choice of a framework is made solely on pragmatic grounds), thereby rejecting the metaphysical dimension of realism (as in Carnap 1950). 45

45 Chakravartty (2017). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-realism/

This means that positivism is generally seen to imply antirealist views of science and mathematics, preferring as Carnap says in “Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology”:

Empiricists are in general rather suspicious with respect to any kind of abstract entities like properties, classes, relations, numbers, propositions, etc. They usually feel much more in sympathy with nominalists than with realists (in the medieval sense). As far as possible they try to avoid any reference to abstract entities and to restrict themselves to what is sometimes called a nominalistic language, i.e., one not containing such references. 46

46 Carnap (1950), p. 1.

Positivists have instrumentalist (antirealist) views about the models science produces, given that they are constructed from abstractions and involve the epistemological limitations of induction and theory change. As a qualified sort of empiricism that supports the primacy of the scientific method, positivism is sometimes equated with scientism (often derogatorily) if one takes it to claim that science is the only way to attain knowledge.

Russell:

Modern analytical empiricism […] differs from that of Locke, Berkeley, and Hume by its incorporation of mathematics and its development of a powerful logical technique. It is thus able, in regard to certain problems, to achieve definite answers, which have the quality of science rather than of philosophy. It has the advantage, in comparison with the philosophies of the system-builders, of being able to tackle its problems one at a time, instead of having to invent at one stroke a block theory of the whole universe. Its methods, in this respect, resemble those of science. 47

47 Russell (2004), p. 742–3.

Schlick:

If we say, as was frequently said of old, that metaphysics is the theory of “true being”, of “reality in itself”, of “transcendent being” this obviously implies a (contradictory), spurious, lesser, apparent being; as has indeed been assumed by all metaphysicians since the time of Plato and the Eleatics. This apparent being is the realm of “appearances”, and while the true transcendent reality is to be reached only with difficulty, by the efforts of the metaphysician, the special sciences have to do exclusively with appearances which are perfectly accessible to them. The contrast in cognizability of these two “modes of being” is then explained by the fact that the appearances are immediately known, “given”, to us, while metaphysical reality must be inferred from them in some roundabout manner. And thus we seem to arrive at a fundemental concept of the positivists, for they always speak of the “given”, and usually formulate their fundamental principle in the proposition that the philosopher as well as the scientist must always remain within the given, that to go beyond it, as the metaphysician attempts, is impossible or senseless. 48

48 Schlick (1948), p. 479.

In a more general sense, positivism is aligned with naturalism, the meta-philosophy that roughly says that science should inform and bootstrap our philosophical claims. Naturalists, having a more broadly aligned and various support for science, may not have such exclusive views of epistemology or such eliminative views of metaphysics. Many naturalists are instead realists about science, math, and/or ethics, for example following a version of structural realism about the discoveries from science, capturing and constraining real structures in nature.

Creath:

contemporary philosophers promote a kind of naturalism, and by so doing they follow both the precept and the example of the logical empiricists. 49

4.7.2 Theses

- Hume’s fork, the analytic/synthetic distinction

- Verification theory of meaning: the meaning of a proposition is the means to verify it. All statements that cannot be empirically verified in principle are meaningless.

- AKA the Verification Principle

- Scheinproblem = Pseudo-problem

- See also: Rejection of a priori metaphysics

- Carnap’s principle of tolerance

- Unity of science

50 Carnap (1937a), p. 51.

51 Leitgeb & Carus (2020), Supplement H: Tolerance, Metaphysics, and Meta-Ontology.

52 Carnap (1938).

53 Potochnik (2011).

Orthodox logical positivism:

— panu raatikainen (&commm;panuraatikainen) April 3, 2020

1) only verifiable statements re meaningful;

2) all legitimate statements are translatable to observational language (different interpretations);

3) unity of science (different interpretations). 1/X

TODO: list thesis from the Vienna Circle manifesto.

Neatness and clarity are striven for, and dark distances and unfathomable depths rejected. In science there are no ‘depths’ there is surface everywhere: all experience forms a complex network, which cannot always be surveyed and, can often be grasped only in parts. Everything is accessible to man; and man is the measure of all things. Here is an affinity with the Sophists, not with the Platonists; with the Epicureans, not with the Pythagoreans; with all those who stand for earthly being and the here and now. The scientific world-conception knows no unsolvable riddle. Clarification of the traditional philosophical problems leads us partly to unmask them as pseudo-problems, and partly to transform them into empirical problems and thereby subject them to the judgment of experimental science. The task of philosophical work lies in this clarification of problems and assertions, not in the propounding of special ‘philosophical’ pronouncements. The method of this clarification is that of logical analysis. 54

54 Hahn, Neurath, & Carnap (1973), §2.

Schlick:

Stating the meaning of a sentence amounts to stating the rules according to which the sentence is to be used, and this is the same as stating the way in which it can be verified (or falsified). The meaning of a proposition is the method of its verification. 55

55 Schlick (1936), p. 341.

Schlick:

The fundamental principle of the positivist then seems to run: “Only the given is real”. 56

56 Schlick (1948), p. 480.

Fetzer:

From an historical perspective, logical positivism represents a linguistic version of the empiricist epistemology of David Hume (1711-76). It refines his crucial distinctions of “relations between ideas” and “matters of fact” by redefining them relative to a language \(L\) as sentences that are analytic-in-\(L\) and synthetic-in-\(L\), respectively. His condition that significant ideas are those which can be traced back to impressions in experience that gave rise to them now became the claim that synthetic sentences have to be justified by derivability from finite classes of observation sentences. 57

57 Fetzer (2017).

More:

- Mauro Murzi’s pages on Philosophy of Science: Logical positivism

- Caulton, A. (2014). Lecture notes: Logical positivism/empiricism.

4.7.3 Early positivism

4.7.3.1 Bernard Bolzano

- Bernard Bolzano (1781-1848)

- Wissenschaftslehre (Theory of Science) (1837)

4.7.3.2 Auguste Comte

- Auguste Comte (1798-1857) coined “positivism”

- Comte and Mill

J.S. Mill summarizing Comte’s positivism:

The fundamental doctrine of a true philosophy, according to M. Comte, and the character by which he defines Positive Philosophy, is the following:—We have no knowledge of anything but Phaenomena; and our knowledge of phaenomena is relative, not absolute. We know not the essence, nor the real mode of production, of any fact, but only its relations to other facts in the way of succession or of similitude. These relations are constant; that is, always the same in the same circumstances. The constant resemblances which link phaenomena together, and the constant sequences which unite them as antecedent and consequent, are termed their laws. The laws of phaenomena are all we know respecting them. Their essential nature, and their ultimate causes, either efficient or final, are unknown and inscrutable to us. 58

58 Mill (1865), part 1.

Comte on the unknowability of the composition of stars:

On the subject of stars, all investigations which are not ultimately reducible to simple visual observations are … necessarily denied to us. While we can conceive of the possibility of determining their shapes, their sizes, and their motions, we shall never be able by any means to study their chemical composition or their mineralogical structure … Our knowledge concerning their gaseous envelopes is necessarily limited to their existence, size … and refractive power, we shall not at all be able to determine their chemical composition or even their density… I regard any notion concerning the true mean temperature of the various stars as forever denied to us. 59

59 Comte (1835), Translation of passage taken from:

https://faculty.virginia.edu/rwoclass/astr1210/comte.html

(He was wrong!)

- Feigl, H. (1981). The origin and spirit of logical positivism. 60

- Later in life, Comte founded the Religion of Humanity.

60 Feigl (1981).

4.7.3.3 Ernst Mach

- Ernst Mach (1838-1916)

- Richard Avenarius (1843-1896)

- Empirio-criticism

- Popper, K.R. (1953). A note on Berkeley as precursor of Mach. 61

61 Popper (1953).

4.7.3.4 Franz Brentano

- Franz Brentano (1838-1917)

4.7.3.5 Ludwig Boltzmann

- Ludwig Boltzmann (1844-1906)

4.7.3.6 Gottlob Frege

- Gottlob Frege (1848-1925)

- Not exactly positivist, but drove the logicism project that influenced logical positivism.

- Concept-script (Begriffsschrift) (1879)

- On sense and reference (Über Sinn und Bedeutung) (1892)

- Frege’s context principle: “Only in the context of a sentence do words have meaning” 62

62 Reck (2005).

4.7.3.7 Ludwig Wittgenstein

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

- The linguistic turn

- Gustav Bergmann (1906-1987)

Wittgenstein studied with, was influenced by, and influenced:

- Bertrand Russell & Afred North Whitehead

- Principia Mathematica (1910)

- George Edward Moore

- Friedrich Waismann (1896-1959)

Wittgenstein in a letter to Russell in 1913:

The big question now is, how must a system of signs be constituted in order to make every tautology recognizable as such IN ONE AND THE SAME WAY? This is the fundamental problem of logic! 63

63 McGuinness (2008), p. 59.

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) 64

64 Wittgenstein (1961).

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus [is] the only philosophy book that Wittgenstein published during his lifetime. It claimed to solve all the major problems of philosophy and was held in especially high esteem by the anti-metaphysical logical positivists. The Tractatus is based on the idea that philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of the logic of language, and it tries to show what this logic is. Wittgenstein’s later work, principally his Philosophical Investigations, shares this concern with logic and language, but takes a different, less technical, approach to philosophical problems. This book helped to inspire so-called ordinary language philosophy. 65

65 Richter (2004). https://iep.utm.edu/wittgens/

- Wittgenstein originally wrote the work in German, titled Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung (Logical-Philosophical Treatise), published in 1921.

- For the English translation, Moore suggested the Latin title Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a nod to Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus.

- English translations:

- Wittgenstein presented the Tractatus as his PhD thesis, defended in his viva at Cambridge in June of 1929.

- The picture theory of meaning

- a correspondence theory of truth

- Daitz, E. (1953). The picture theory of meaning. 66

- Keyt, D. (1964). Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language. 67

- There is a one-to-one correspondence between the parts of a proposition and the objects of the state of affairs pictured by the proposition (4.04).

- Propositions are linear structures.

- Every possible state of affairs can be expressed in language.

- Gaskin, R. (2009). Realism and the picture theory of meaning. 68

- Discusses realism in John McDowell’s “minimal empiricism” and Wittgenstein’s picture theory.

- Logical atomism

- Russell’s interpretation of the Tractatus

- Analyticity

- Russell, B. (1919). The philosophy of logical atomism: Lectures 7-8. 69

- Verifiability and quietism

- Anti-metaphysics that impressed the logical positivists

- Wittgenstein’s Tractatus was read by and greatly influenced The Vienna Circle. While Wittgenstein had relations with them, he never participated in the meetings lead by Schlick. (TODO:ref)

- TODO: While the Tractatus does focus on verifiability as an anti-metaphysical criterion, it doesn’t seem that he ever identified with positivism.

- TODO: Most consider Wittgenstein’s early views to follow a kind of logicism that is ultimately anti-realist; but to me, there appears to be an interpretation of that Wittgenstein’s early views of structure that ultimately follow some kind of platonism, the correspondence theory of truth, and a sense of realism.

- Ogden, C.K. & Richards, I.A. (1923). The Meaning of Meaning. 70

- Wittgenstein, L. (1929). Some remarks on logical form. 71

- Only academic paper published by Wittgenstein.

- During a period of transition from his early thought in the Tractatus and his later thought in PI.

- Ian Ground, Stephen Mulhall, & Chon Tejedor. (2018). Video: The Young Wittgenstein.

- Limbeck-Lilienau, C. (2019). Talk: Sources on Wittgenstein: the Nachlasses of Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap and Friedrich Waismann.

66 Daitz (1953).

67 Keyt (1964).

68 Gaskin (2009).

69 Russell (1919).

70 Ogden & Richards (1989).

71 Wittgenstein (1929).

Wittgenstein’s scientific attitude summarized in the Vienna Circle manifesto:

Wittgenstein explaining the point of the Tractatus in a letter to Russell:

The main point is the theory of what can be expressed (gesagt) by propositions—i.e. by language (and, which comes to the same thing, what can be thought) and what can not be expressed by propositions, but only shown (gezeigt); which, I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy. 73

73 Anscombe (1959), p. 161.

Gaskin:

The realism implicit in the idea of answerability to the world contrasts with a pragmatist approach, such as that advocated by Richard Rorty, according to which subjects are answerable in judgement not to the world, but to other judging subjects. 74

74 Gaskin (2009), p. 53.

Later Wittgenstein made a significant shift. See Ordinary language philosophy.

4.7.3.8 Frank P. Ramsey

- F.P. Ramsey (1903-1930)

- Ramsey, F.P. (1923). Review of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. 75

- Ramsey, F.P. (1925). Universals. 76

- Ramsey, F.P. (1926). Foundations of mathematics. 77

- Ramsey, F.P. (1927). Facts and propositions. 78

- Lewis, D. (1970). How to define theoretical terms. 79

- Ramsey-Lewis method

4.7.3.9 Emile Durkheim

- Émile Durkheim (1858-1917)

- Modern sociology

- Houghton, T. (2011). Does positivism really ‘work’ in the social sciences? 80

80 Houghton (2011).

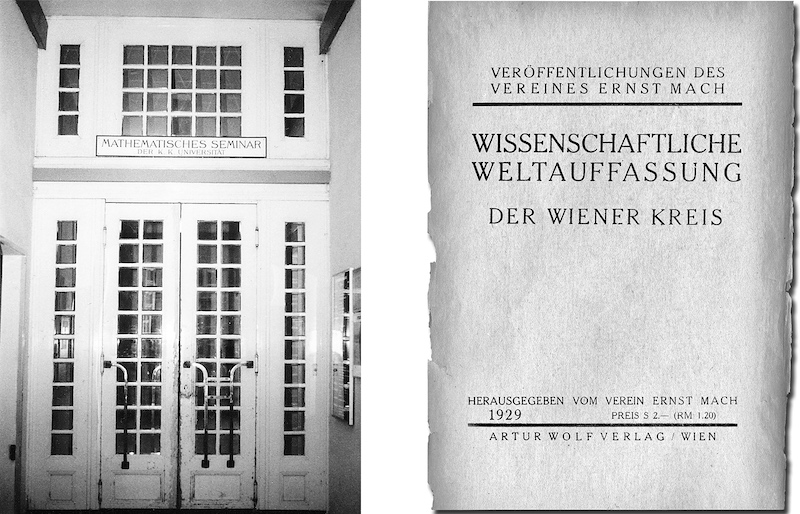

4.7.4 The Vienna Circle

- Logical positivism/empiricism

- The beginning of The Circle was an unnamed gathering in Vienna founded by Hans Hahn in 1907. 81

- Attened by Philipp Frank, Otto Neurath, and Richard von Mises.

- Ernst Mach Society

- Carnap

- Oxford Bibliographies: Rudolf Carnap

- From 1910–1914, Carnap studied philosophy, physics and mathematics at the universities of Jena and Freiburg.

- Carnap studied mathematical logic under Frege at Jena.

- Carnap met Reichenbach at the “Erlangen Conference”, March 6-13, 1923.

- WWI lasted from 1914–1918.

- Group of philosophers lead by Moritz Schlick that met regularly at the University of Vienna from 1924–1936.

- Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath, Hans Hahn, Herbert Feigl, Philipp Frank, Friedrich Waismann, Gustav Bergmann, Kurt Gödel, Victor Kraft, and others.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein and Karl Popper corresponded with the circle but did not attend.

- The circle discussed Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico Philosophicus in detail during the years 1925–1927.

- The circle was named by Neurath82 “The Vienna Circle” when its manifesto was published as a pamplet in 1929 at The First Conference for the Epistemology of the Exact Sciences, in Prague.

- Schlick, M. (1925). General Theory of Knowledge. 83

- In 1926, Carnap arrives in Vienna as a Privatdozent and joins the Vienna Circle.

- Carnap, R. (1928). The Logical Structure of the World (Der Logische Aufbau der Welt). 84

- Rational reconstruction

- Explication

- Lewis, D.K. (1969). Policing the Aufbau. 85

- Chalmers, D.J. (2020). Carnap’s Second Aufbau and David Lewis’s Aufbau. 86

- Hahn, H., Neurath, O., & Carnap, R. (1929). The scientific conception of the world: The Vienna Circle. 87

- Wissenschaftliche Weltauffassung: Der Wiener Kreis

- The Vienna Circle’s manifesto

- Cassirer-Heidegger debate in Davos (1929)

- In 1930 the Vienna Circle and the Berlin Circle took over the journal Annalen der Philosophie and made it the main journal of logical empiricism under the title Erkenntnis, edited by Carnap and Reichenbach.

- Schlick, M. (1930). The turning point in philosophy. 88

- Carnap, R. (1932). The elimination of metaphysics through logical analysis of language. 89

- Carnap, R. (1932). On protocol sentences. 90

- Schlick, M. (1933). Positivism and realism. 91

- Blumberg, A.E. & Feigl, H. (1930). Logical positivism: A new movement in European philosophy. 92

- First survey of logical positivism published in English?

- Second Conference on the Epistemology of the Exact Sciences (1930)

- A.J. Ayer (1910-1989)

- Ayer, A.J. (1936). Language, Truth, and Logic. 93

- Helped the spread of positivism in British academia.

- The murder of Schlick in 1936 by a former student put an end to the Vienna Circle in Austria.

82 Edmonds (2020), p. 90.

83 Schlick (1974).

84 Carnap (2003).

85 D. K. Lewis (1969).

86 D. J. Chalmers (2020).

87 Hahn et al. (1973).

88 Schlick (1959).

89 Carnap (1959).

90 Carnap (1987).

91 Schlick (1948).

92 Blumberg & Feigl (1931).

93 Ayer (1936).

Discussions of overcoming metaphysics:

- Sachs, C.B. (2011). What is to be Overcome? Nietzsche, Carnap, and modernism as the overcoming of metaphysics. 94

- Creath, R. (2023). What was Carnap rejecting when he rejected metaphysics?. 95

Surveys:

- Coffa, A. (1991). The Semantic Tradition from Kant to Carnap: To the Vienna Station. 96

- Stadler, F. (1998). Vienna Circle. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 97

- Murzi, M. (2004). Vienna Circle. In Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 98

- Stadler, F. (2015). The Vienna Circle: Studies in the origins, development, and influence of Logical Empiricism. 99

- Sigmund, K. (2017). Exact Thinking in Demented Times: The Vienna Circle and the epic quest for the foundations of science. 100

- Review: Cat, J. (2017). How Viennese scientists fought the dogma, propaganda and prejudice of the 1930s.

- Verhaegh, S. (2019). The American reception of logical positivism: First encounters (1929-1932). 101

- Edmonds, D. (2020). The Murder of Professor Schlick: The Rise and Fall of the Vienna Circle. 102

- Springer book series: Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook

4.7.5 The Berlin Circle

- Hans Reichenbach (1891-1953)

- Originated with Hans Reichenbach’s seminars held from October 1926 at the University of Berlin.

- In 1928, Reichenbach founded the Berlin Group, which was called Die Gesellschaft für empirische Philosophie (Society for Empirical Philosophy).

- Walter Dubislav, Alexander Herzberg, Kurt Grelling, Carl Gustav Hempel, Richard von Mises, and David Hilbert.

- Reichenbach, H. (1936). Logistic empiricism in Germany and the present state of its problems. 103

- Rescher, N. (2006). The Berlin School of logical empiricism and its legacy. 104

- Milkov, N. (2013). The Berlin Group and the Vienna Circle: Affinities and divergences. 105

- Hempel and his students at the University of Pittsburg are an outgrowth of the Berlin Circle.

- Creath, R. (2017). Logical empiricism. 106

103 Reichenbach (1936).

104 Rescher (2006).

105 Milkov (2013).

106 Creath (2017a). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-empiricism/

TODO: Note any differences between:

- Positivism - Comte, Mach

- Logical positivism - Vienna Circle

- Logical empiricism - Reichenbach’s preferred term 107

4.7.6 Later positivism

- In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

- In 1933, Reichenbach moved to Turkey to become chief of the Department of Philosophy at the University at Istanbul.

- In 1935, Carnap emigrated to the United States and became a professor at the University of Chicago.

- In 1937, Carl Gustav Hempel joined Carnap at U Chicago as his assistant.

- Carnap, R. (1936). Testability and meaning. 108

- Argued to replace verification with confirmation.

- Carnap spent many years trying to develop a theory of degree of confirmation but was never able to satisfactorily formulate a model. 109

- Carnap, R. (1937). Testability and meaning—continued. 110

- International Encyclopedia of Unified Science

- Chief editors: Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap, and Charles W. Morris

- Only the first volume of Foundations of the Unity of Science, in two volumes, was ever published between 1938 and 1969.

- Neurath, O., Carnap, R., & Morris, C.W. (1955). International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Vol. 1. 111

- Anschluss: The annexation of Austria by the Third Reich on March 13, 1938.

- In 1938, Reichenbach emigrated to the US and became a professor at UCLA.

- Hilary Putnam and Wesley Salmon were among Reichenbach’s students at UCLA.

- The Fifth International Congress for the Unity of Science met at Harvard in 1939.

- On September 1, 1939, two days before the start of the congress, Germany invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Germany.

- Many European attendees did not return to Europe.

- Carnap joined UCLA in 1954, the year after Reichenbach died.

- Carnap died in 1970.

- Surveys of Carnap

- Carnap, R. & Schilpp, P.A. (1963). The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. 112

- AKA the “Schilpp volume”

- Paul Arthur Schilpp (1897-1993)

- Kazemier, B.H. & Vuysje, D. (1962). Logic and Language: Studies Dedicated to Professor Rudolf Carnap on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. 113

- Buck, R.C. & Cohen, R.S. (1971). PSA 1970: In Memory of Rudolf Carnap Proceedings of the 1970 Biennial Meeting Philosophy of Science Association. 114

- Hintikka, J. (1975). Rudolf Carnap, Logical Empiricist. 115

- Friedman, M. (1999). Reconsidering Logical Positivism. 116

- Awodey, S. & Klein, C. (2004). Carnap Brought Home: The View from Jena. 117

- Friedman, M. & Creath, R. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Carnap. 118

- Carus, A.W. (2008). Carnap and Twentieth-Century Thought. 119

- Creath, R. (2012). Rudolf Carnap and the Legacy of Logical Empiricism. 120

- Ebbs, G. (2017). Carnap, Quine, and Putnam on Methods of Inquiry. 121

- Verhaegh, S. (2020). Coming to America: Carnap, Reichenbach and the great intellectual migration. 122

- Richardson, A. & Tuboly, A.T. (2024). Interpreting Carnap: Critical Essays. 123

- Carnap, R. & Schilpp, P.A. (1963). The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap. 112

- Waismann, F. (1956). How I see philosophy.

- Morris, K.J. (2019). “How I see philosophy”: An apple of discord among Wittgenstein scholars. 124

108 Carnap (1936).

109 Murzi (2001). https://iep.utm.edu/carnap/

110 Carnap (1937b).

111 Neurath, Carnap, & Morris (1955).

112 Carnap & Schilpp (1963).

113 Kazemier & Vuysje (1962).

114 Buck & Cohen (1971).

115 Hintikka (1975).

116 Friedman (1999).

117 Awodey & Klein (2004).

118 Friedman & Creath (2007).

119 Carus (2008).

120 Creath (2012).

121 Ebbs (2017).

122 Verhaegh (2020).

123 Richardson & Tuboly (2024).

124 Morris (2019).

4.7.6.1 Carnap on language and ontology

- Carnap, R. (1937). The Logical Syntax of Language. (LSL) 125

- Coffa, A. (1987). Carnap, Tarski and the search for truth. 126

- Wagner, P. (2009). Carnap’s Logical Syntax of Language. 127

- Fowler, S. (2010). LSL in a nutshell. 128

- Blanchette, P. (2013). Talk: Frege and Gödel on mathematics as syntax.

- Creath, R. (2017). The logical and the analytic. 129

- Leitgeb & Carus: “talk of meaning should in any case be eschewed in favor of talk of syntax” 130

- Carnap, R. (1950). Empiricism, semantics, and ontology. (ESO) 131

- Lavers, G. (2004). Carnap, semantics and ontology. 132

- Lavers, G. (2015). Carnap, Quine, quantification and ontology. 133

- Nado, J. (2024). Truth in philosophy: a conceptual engineering approach. 134

125 Carnap (1937a).

126 Coffa (1987).

127 Wagner (2009).

128 Fowler (2010).

129 Creath (2017b).

130 Leitgeb & Carus (2020), Supplement G: Logical Syntax of Language.

131 Carnap (1950).

132 Lavers (2004).

133 Lavers (2015).

134 Nado (2024).

Carnap’s principle of tolerance:

Principia of Tolerance: It is not our business to set up prohibitions, but to arrive at conventions. 135

135 Carnap (1937a), §17.

and

In logic, there are no morals. Everyone is at liberty to build up his own logic, i.e., his own form of language, as he wishes. All that is required of him is that, if he wishes to discuss it, he must state his methods clearly, and give syntactical rules instead of philosophical arguments. 136

136 Carnap (1937a), §17.

Carnap in ESO:

An alleged statement of the reality of the system of entities is a pseudo-statement without cognitive content. To be sure, we have to face at this point an important question; but it is a practical, not a theoretical question; it is the question of whether or not to accept the new linguistic forms. The acceptance cannot be judged as being either true or false because it is not an assertion. It can only be judged as being more or less expedient, fruitful, conducive to the aim for which the language is intended. 137

137 Carnap (1950), p. 7.

Discussion:

- Quine, W.V.O. (1960). Carnap and logical truth. 138

- Steinberger, F. (2016). How tolerant can you be? Carnap on rationality. 139

- Leitgeb, H. & Carus, A. (2020). Rudolf Carnap. SEP. 140

- Baker, K. (2023). Video: Metaphysics - Carnap on Ontology.

4.7.6.2 Neurath’s boat

- Coherentism

- Anti-foundationalism

- Duhem-Quine thesis

Neurath:

Duhem has shown with special emphasis that every statement about any happening is saturated with hypotheses of all sorts and that these in the end are derived from our whole world-view. We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom. Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support. In this way, by using the old beams and driftwood, the ship can be shaped entirely anew, but only by gradual reconstruction. 141

141 Neurath (1973), p. 199.

and

There is no way to establish fully secured, neat protocol statements as starting points of the sciences. There is no tabula rasa. We are like sailors who have to rebuild their ship on the open sea, without ever being able to dismantle it in dry-dock and reconstruct it from the best components. Only metaphysics can disappear without trace. Imprecise ‘verbal clusters’ [‘Ballungen’] are somehow always part of the ship. If imprecision is diminished at one place, it may well re-appear at another place to a stronger degree. 142

142 Neurath (1983), p. 92.

Quine:

Neurath has likened science to a boat which, if we are to rebuild it, we must rebuild plank by plank while staying afloat in it. The philosopher and the scientist are in the same boat. If we improve our understanding of ordinary talk of physical things, it will not be by reducing that talk to a more familiar idiom; there is none. It will be by clarifying the connections, causal or otherwise, between ordinary talk of physical things and various further matters which in turn we grasp with help of ordinary talk of physical things. 143

143 Quine (1960b), p. 3.

See also:

4.7.6.3 Reichenbach

On logical empiricism and Reichenbach at UCLA:

Part of the movement’s legacy lies in contemporary philosophy of science. In the US nearly all philosophers of science can trace their academic lineages to Reichenbach. Most were either his students or students of his students and so on. His scientific realism inspired a generation of philosophers, even those clearly outside the movement. Even the reaction against various forms of realism that have appeared in recent decades have roots in the logical empiricist movement. Moreover, philosophers of science are expected to know a great deal of the science about which they philosophize and to be cautious in telling practicing scientists what concepts they may or may not use. In these respects and others contemporary philosophers promote a kind of naturalism, and by so doing they follow both the precept and the example of the logical empiricists. 144

144 Creath (2017a). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-empiricism/

and

Among his many students were Hempel, Putnam, and W. Salmon, and so almost all philosophy of science in the US can trace its academic lineage to Reichenbach. Though interested in social and educational reform, he worked primarily in philosophy of physics. He developed and defended a frequency theory of probability, and emphasized both scientific realism and the importance of causality and causal laws. 145

145 Creath (2017a). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-empiricism/

Reichenbach:

Reichenbach on probability:

locates the probability objectively “out in nature” so to speak, and this comports well with Reichenbach’s scientific realism. 148

148 Creath (2017a). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-empiricism/

- TODO: later Reichenbach was a scientific realist.

- Psillos, S. (2011). On Reichenbach’s argument for scientific realism. 149

149 Psillos (2011).

4.7.7 Neopositivism

- Friedrich Stadler (b. 1951) - Director of the Vienna Circle Society

- Richard Creath (b. 1947) - Editor of the Quine-Carnap Correspondence (1990)

- Ladyman, J. & Ross, D. (2007). Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalised.

- Self-identify as neo-positivists 150

- Ney, A. (2012). Neo-positivist metaphysics. 151

- Leitgeb, H. (2023). Vindicating the verifiability criterion. 152

- Richardson, A. (2023). Logical Empricism as Scientific Philosophy 153

Final words of Ladyman and Ross (2007):

Of all the main historical positions in philosophy, the logical positivists and logical empiricists came closest to the insights we have urged. Over-reactions to their errors have led metaphysicians over the past few decades into widespread unscientific and even anti-scientific intellectual waters. We urge them to come back and rejoin the great epistemic enterprise of modern civilization. 154

154 Ladyman et al. (2007), p. 310.

Also:

- Movements in “positivism”: positivists.org/blog/movements

- Posted at: r/PhilosophyofScience: What is positivism?

Vienna Circle / Berlin Circle / logical positivism scholars:

- Steve Awodey (b. 1959)

- Herbert G. Bohnert (1918-1984)

- André W. Carus

- Alberto Coffa (1935-1984)

- Richard Creath (b. 1947)

- Christian Damböck (b. 1968)

- Michael Friedman (b. 1947)

- Ronald Giere (1938-2020)

- Warren Goldfarb (b. 1949)

- Jaakko Hintikka (1929-2015)

- Benjamin Marschall

- Brian F. McGuinness (1927-2019)

- Thomas Mormann (b. 1951)

- Mauro Murzi (b. 1961)

- Matthias Neuber (b. 1970)

- Panu Raatikainen

- Alan Richardson

- Thomas G. Ricketts

- Karl Sigmund (b. 1945)

- Olaf Simons (b. 1961)

- Friedrich Stadler (b. 1951)

- Thomas Uebel (b. 1952)

- Sander Verhaegh (b. 1986)

- Andreas Vrahimis

- Pierre Wagner (b. 1963)

- Sandy L. Zabell (b. 1947)

See also:

4.8 Postpositivism

4.8.1 Introduction

Various reactions to positivism.

- Karl Popper (1902-1994)

- Brian F. McGuinness (1927-2019)

- The Myth of the Framework (1994)

- Brian F. McGuinness (1927-2019)

- Willard Van Orman Quine (1908-2000)

- Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996)

- Imre Lakatos (1922-1974)

- Hilary Putnam (1926-2016)

- Nancy Cartwright (b. 1944)

- TODO: Khanna 155

- de Swart 156

- Positivism dispute

4.8.2 Attack on the analytic/synthetic distinction

Among the developments that led to the revival of metaphysical theorizing were Quine’s attack on the analytic/synthetic distinction, which was generally taken to undermine Carnap’s distinction between existence questions internal to a framework and those external to it. 157

- Carnap’s internal vs external questions, (ESO), again

- Quine, W.V.O. (1951). Two dogmas of empiricism. 158

- Analytic/synthetic distinction

- Reductionism (verification theory of meaning)

- Quine’s critique is decribed well in Stalnaker, R.C. (2003). Ways a World Might Be. 159

Quine on our pale gray lore:

The lore of our fathers is a fabric of sentences. In our hands it develops and changes, through more or less arbitrary and deliberate revisions and additions of our own, more or less directly occasioned by the continuing stimulation of our sense organs. It is a pale grey lore, black with fact and white with convention. But I have found no substantial reasons for concluding that there are any quite black threads in it, or any white ones. 160

160 Quine (1960a), p. 374.

4.8.2.1 Criticism

Carnap remained optimistic about his views of analyticity, intension, and meaning:

Bar-Hillel points out that the semantical theory of meaning developed recently by logicians is free of these drawbacks. He appeals to the linguists to construct in an analogous way the theory of meaning needed in their empirical investigations. The present paper indicates the possibility of such a construction. The fact that the concept of intension can be applied even to a robot shows that it does not have the psychologistic character of the traditional concept of meaning. 161

161 Carnap (1955), p. 46–47, footnote 7.

Feigl:

4.8.3 Attack on the verification theory of meaning

- Quine, W.V.O. (1960). Word and Object. 165

- Inscrutability of reference

- Indeterminacy of translation

- Ruja, H. (1961). The present status of the verifiability criterion. 166

- Quine, W.V.O. (1963). On simple theories of a complex world. 167

- Putnam, H. (1973). Meaning and reference. 168

- Putnam, H. (1975). The meaning of “meaning”. 169

Nietzsche:

Against positivism, which would stand by the position “There are only facts”, I would say: no, there are precisely no facts, only interpretations. We can establish no fact “in itself”: it is perhaps nonsense to want such a thing. You say “Everything is subjective”: but that is already an interpretation, the “subject” is not anything given, but something invented and added, something stuck behind… To the extent that the word “knowledge” [Erkenntnis] has any sense, the world is knowable: but it is interpretable differently, it has no sense behind it, but innumerable senses, “perspectivism”. It is our needs that interpret the world: our drives and their to and fro. Every drive is a kind of domination, every one has its perspective, which it would force on all other drives as a norm. 170

170 Nietzsche (Notebook 7 [60]. KSA 12.315). See: Guyer & Horstmann (2021).

Putnam:

If language is a tool, it is a tool like an ocean liner, which requires many people cooperating (and participating in a complex division of labor) to use. What gives one’s words the particular meanings they have is not just the state of one’s brain, but the relations one has to both one’s non-human environment and to other speakers. 171

171 Putnam (1997).

4.8.4 Duhem-Quine thesis

- Claims that a hypothesis can never be tested in isolation.

- Confirmation holism

- Web of belief

More:

- Schuldenfrei, R. (1972). Quine in perspective. 172

- Quine, W.V.O., Schilpp, P.A., & Hahn, L.E. (1986). The Philosophy of W.V. Quine. 173

- Quine-Carnap Correspondence (1990) 174

- Quine, W.V.O. (1991). Two dogmas in retrospect. 175

- Yablo, S. & Gallois, A. (1998). Does ontology rest on a mistake? 176

- Frost-Arnold, G. (2013). Carnap, Tarski, and Quine at Harvard: Conversations on Logic, Mathematics, and Science. 177

- Warren, J. (2016). Internal and external questions revisited. 178

- Warren, J. (2016). Revisiting Quine on truth by convention. 179

172 Schuldenfrei (1972).

173 Quine, Schilpp, & Hahn (1986).

174 Quine & Carnap (1990).

175 Quine (1991).

176 Yablo & Gallois (1998).

177 Frost-Arnold (2013).

178 Warren (2016a).

179 Warren (2016b).

Russell:

What is recorded as the result of an experiment or observation is never the bare fact perceived, but this fact as interpreted by the help of a certain amount of theory. 180

180 Russell (1992), p. 187.

See also:

- The introduction to the analytic/synthetic distinction in the Outline on the scientific method.

- Neurath’s boat

4.8.5 Theory change

- Poincaré

- Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996)

- Paradigm shifts

- Normal science and revolutionary science

- Incommensurability

- Sankey 181

- Imre Lakatos (1922-1974)

- Scientific research programmes

- Paul Feyerabend (1924-1994)

- Epistemological anarchism

- Larry Laudan (b. 1941)

- Scientific research traditions

- Pessimistic meta-induction (PMI)

- Science cannot be value free

- Field, H. (1974). Theory change and the indeterminacy of reference. 182

4.8.6 Ordinary language philosophy

- Late Wittgenstein

- Instrumentalist and pragmatist

- Blue and Brown Books (1933-35)

- Lecture notes and notes dictated, mimeographed as a few copies and circulated during Wittgenstein’s lifetime.

- At the end of his fellowship at Cambridge in the summer of 1936, Wittgenstein went to Norway and attempted to revise the Brown Book for publication, but failed.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. 183

- The original version of PI was drafted in late 1936, known to scholars as the Urfassung (original version).

- Published posthumously in 1953.

- Edited and translated to English by G.E.M. Anscombe.

- Opens with a discussion of the Augustinian picture of language and is critical of it.

- Frege’s context principle

- Language games; Meaning as use.

- Duck-rabbit; “seeing that” vs “seeing as”.

- An important project is to understand the differences between early (TLP) and late (PI) Wittgenstein. It is quite the about-face.

- TLP: The picture theory of meaning. Language has a structure that can be mapped onto (meaning) the logical structure of the world. Logicism.

- PI: The meaning of a word is its use. Constructivism/Intuitionism.

- The rule-following paradox 184

- Wittgenstein, L. (1969). On Certainty. 185

- Video: Sugrue, M. (1992). The Latter Wittgenstein: The Philosophy of Language.

- Gilbert Ryle (1900-1976)

- P.F. Strawson (1919-2006)

- Strawson, P.F. (1950). On referring. 186

- The Bounds of Sense: An Essay on Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1966)

- Clifford Geertz (1926-2006)

- The Interpretation of Cultures (1973)

- Stanley Cavell (1926-2018)

- Must We Mean What We Say? (1969) 187

- The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (1979)

- Saul Kripke (1940-2022)

- Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language (1982)

- Distinguishes the views of Wittgenstein, Kripke, and Kripkenstein

- Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language (1982)

- Emma Borg

- Borg, E. (2007). Minimal Semantics. 188

183 Wittgenstein (2009).

184 Wittgenstein (2009), §201.

185 Wittgenstein (1969).

186 Strawson (1950).

187 Cavell (2015).

188 Borg (2007).

Wittgenstein in PI:

Philosophy is a struggle against the bewitchment of our understanding by the resources of our language. 189

189 Wittgenstein (2009), §109.

and

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (4.5): “The general form of propositions is: This is how things are.” — That is the kind of proposition one repeats to oneself countless times. One thinks that one is tracing nature over and over again, and one is merely tracing round the frame through which we look at it. 190

190 Wittgenstein (2009), §114.

See also:

4.8.7 The “death” of positivism

- Anti-positivism, Kuhn, Popper

- post-structuralism, postmodernism (continental)

- Hempel, C.G. (1950). Problems and changes in the empiricist criterion of meaning. 191

- In 1967 John Passmore reported that: “Logical positivism, then, is dead, or as dead as a philosophical movement ever becomes.” 192

- A.J. Ayer (1910-1989)

- Suppe (2000): Death of positivism was a talk by Carl Hempel on March 26, 1969. 193

- Edmonds, D. (2020). The Murder of Professor Schlick: The Rise and Fall of the Vienna Circle. 196

191 Hempel (1950).

192 Passmore (1967) and Creath (2017a) https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-empiricism/

193 Suppe (2000).

194 Hempel (1974).

195 Clarke & Primo (2004).

196 Edmonds (2020).

Clarke & Primo:

Following Suppe (2000), we date the demise of logical positivism to March 26, 1969—opening night of the Illinois Symposium on the Structure of Scientific Theories. 197

197 Clarke & Primo (2004).

Ayer:

Bunge:

Logical positivism was progressive compared with the classical positivism of Ptolemy, Hume, d’Alembert, Compte, John Stuart Mill, and Ernst Mach. It was even more so by comparison with its contemporary rivals—neo-Thomisism, neo-Kantianism, intuitionism, dialectical materialism, phenomenology, and existentialism. However, neo-positivism failed dismally to give a faithful account of science, whether natural or social. It failed because it remained anchored to sense-data and to a phenomenalist metaphysics, overrated the power of induction and underrated that of hypothesis, and denounced realism and materialism as metaphysical nonsense. Although it has never been practiced consistently in the advanced natural sciences and has been criticized by many philosophers, notably Popper (1959 [1935], 1963), logical positivism remains the tacit philosophy of many scientists. Regrettably, the anti-positivism fashionable in the metatheory of social science is often nothing but an excuse for sloppiness and wild speculation. 199

199 Bunge (1996), p. 317.

Positivism vs critical theory:

- Sachs, C.B. (2020). Why did the Frankfurt school misunderstand logical positivism?

- O’Neill, J. & Uebel, T. (2004). Horkheimer and Neurath: Restarting a disrupted debate. 200

- Vrahimis, A. (2020). Scientism, social praxis, and overcoming metaphysics: A debate between logical empiricism and the Frankfurt School. 201

4.8.8 Lasting influence of positivism

Much ado is made about positivism being “dead”, but its influence is still promenent in philosophy, sociology, and public administration.

Friedman:

Carnap’s influence, in particular, also extended much further: to the widespread application of logical and mathematical methods to philosophical problems more generally, especially in semantics and the philosophy of language. Indeed, as is well known, the ideas of the logical positivists exerted a very substantial influence well beyond the boundaries of professional philosophy, particularly in psychology and the social sciences. It is not too much to say, therefore, that twentieth-century intellectual life would be simply uncrecognizable without the deep and pervasive current of logical positivist thought. 202

202 Friedman (1999), p. xii.

Quine:

Carnap is a towering figure. I see him as the dominant figure in philosophy from the 1930’s onward, as Russell had been in the decades before. 203

203 Quine (1970), p. xxii.

and

Carnap was my greatest teacher… I was very much his disciple for six years. In later years his views went on evolving and so did mine, in divergent ways. But even where we disagreed he was still setting the theme; the line of my thought was largely determined by problems that I felt his position presented. 204

204 Quine (1970), p. xxiii.

- TODO: Positivism affects the structure of education and law

- Whetsell, T.A. & Shields, P.M. (2013). The dynamics of positivism in the study of public administration. 205

- TODO: Connection to the projects of Dewey and pragmatism

- “Positivism and progress” in the Proceedings of the 25th Solvay Conference on Physics (2011) 206

See also:

4.8.9 Realist turn

- A turn towards realism

- Poincaré

- structure

- Reichenbach

- Karl Popper (1902-1994)

- Popper alleged that instrumentalism reduces basic science to what is merely applied science.

- falsifiability over verifiability

- Feigl, H. (1950). Existential hypotheses: Realistic versus phenomenalistic interpretations. 207

- Suppe, F. (1974). The Structure of Scientific Theories. 208

- Sellars

- Saul Kripke (1940-2022)

- Naming directly; causal theory of names; natural kinds

- Putnam, NMA

- John McDowell

- Boyd, R.N. (1983). On the current status of the issue of scientific realism. 209

- Sankey 210

- Talk by Sankey: Scepticism, Relativism and Naturalistic Particularism

- Chisholm’s particularism: start with what is uncontroversially known. Justify epistemic standards second. It’s ok to question beg.

- Claudia Stancati. (2017). Umberto Eco: The philosopher of signs.

Popper:

Instrumentalism can be formulated as the thesis that scientific theories—the theories of the so-called ‘pure’ sciences—are nothing but computational rules (or inference rules); of the same character, fundamentally, as the computation rules of the so-called ‘applied’ sciences. (One might even formulate it as the thesis that “pure” science is a misnomer, and that all science is ‘applied’.) Now my reply to instrumentalism consists in showing that there are profound differences between “pure” theories and technological computation rules, and that instrumentalism can give a perfect description of these rules but is quite unable to account for the difference between them and the theories. 211

211 Popper (1963), p. TODO.

Bunge:

As is well known, conceptual objects have been the undoing of traditional empiricism as well as of vulgar materialism, for they are neither distillates of ordinary experiences nor material objects or properties thereof. To be sure, the empiricist may claim that there are no conceptual objects aside from mental events. But he cannot explain how different minds can grasp the same conceptual objects and why psychology is incapable of accounting for the logical, mathematicaland semantical properties of constructs. And the vulgar materialist (nominalist) will likewise discard conceptual objects and speak instead of linguistic objects—e.g. of terms instead of concepts and of sentences instead of propositions. But he is unable to explain the conceptual invariants of linguistic transformations (e.g. translations) as well as the fact that linguistics presupposes logic and semantics rather than the other way round. Therefore we cannot accept either the empiricist or the nominalist reduction (elimination) of conceptual objects any more than we can admit the idealist claim that they are ideal beings with an autonomous existence. We must look for an alternative consistent with both ontological naturalism and semantical realism. 212

212 Bunge (2012), p. 161.

Sankey:

The Causal-Theoretic Reply to Incommensurability

Assuming the causal theory of reference, one might reply to the incommensurability thesis somewhat as follows. The meaning, in the sense of ‘sense’, of scientific terms may well vary in the course of theoretical change. However, it does not follow that reference must also vary as a result of such change of meaning. For reference is not determined by sense, but by causal chains which link the present use of terms with initial baptisms at which their reference was fixed. So reference does not vary with the changes of descriptive content which occur during theoretical change. Hence, reference is held constant across theoretical transitions, and theories may be compared by means of reference. Thus, there is no referential discontinuity, no incomparability of content, and no incommensurability. 213

213 Sankey (2008), p. 66.

4.9 Pragmatism

4.9.1 Introduction

- Antirealist

- Our confidence comes in continuous amounts. We might as well act as if a claim with a certain confidence is real, however, we really deny realism.

- Meaning is rooted in use.

- Uniquely American philosophical movement.

- Pragmatic theory of truth

4.9.2 History

- Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914)

- The Metaphysical Club (1872)

- “Illustrations of the Logic of Science” in Popular Science Monthly (1877-1878)

- “The Fixation of Belief”

- “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”

- “The Doctrine of Chances”

- “The Probability of Induction”

- “The Order of Nature”

- “Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis”

- Biography: Brent, J. (1993). Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life. 214

- Review of Brent: Oakes, E.T. (1993). Discovering the American Aristotle.

- Auspitz, J.L. (1994). The wasp leaves the bottle: Charles Sanders Peirce. 215

- William James (1842-1910)

- The cash value of truth

- John Dewey (1859-1952)

- George Santayana (1863-1952)

- C.I. Lewis (1883-1964)

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

- Ernest Nagel (1901-1985)

- The Structure of Science (1961)

- Willard Van Orman Quine (1908-2000)

- Quine, W.V.O. (1936). Truth by convention. 216

- Wilfrid Sellars (1921-1989)

- Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (1956) 217

- “The myth of the given”

- Only language can work as a foundation for arguments; non-linguistic sensory perceptions are incompatible with language.

- Critic of foundationalist epistemology

- Sheff, N. (2021). Wilfrid Sellars, sensory experience and the ‘Myth of the Given’.

- Richard Rorty (1931-2007)

- Hilary Putnam (1926-2016)

- Rorty and Putnam

- Ruth Millikan (b. 1933)

- Paul Churchland (b. 1942)

- Daniel C. Dennett (1942-2024)

- Robert Brandom (b. 1950)

- Brandom, R. (1994). Making it Explicit: Reasoning, representing, and discursive commitment. 220

- Sandra Mitchell (b. 1951)

214 Brent (1993).

215 Auspitz (1994).

216 Quine (1936).

217 Sellars (1963).

218 Rorty (1967).

219 Brandom (2000).

220 Brandom (1994).

Peirce:

The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality.

and

Hence, the sole object of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. We may fancy that this is not enough for us, and that we seek not merely an opinion, but a true opinion. But put this fancy to the test, and it proves groundless; for as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied, whether the belief be false or true. 221

221 Peirce (1923).

4.9.3 Discussion

- Haack, S. (1996). We Pragmaticists: Peirce and Rorty in conversation. 222

- Haack, S. (1997). Vulgar Rortyism. 223

- Dennett, D.C. (2006). Higher-order truths about chmess. 224

Consider the following interpretation of the dichotomy between science and engineering: if you can directly see and manipulate the things you’re dealing with, you’re doing engineering, and if not—you need to ask clever indirect questions to get at what you’re really interested in—you’re doing science.

4.10 Postmodernism

4.10.1 Introduction

- Antirealist, relativism

- Conventionalism

- Social constructivism

- Incommensurability, impossibility of translation

- Critical theory

- Post-structuralism

4.10.2 History

- Relativism was previously clearly defended by the ancient Greek sophists

- “Man is the measure of all things” - Protagoras

- Gorgias

- René Girard (1923-2015)

- Jean-François Lyotard (1924-1998)

- The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979)

- “Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives.”

- Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995)

- Michel Foucault (1926-1984)

- Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007)

- Simulacra and Simulation (1981)

- Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)

- Schliesser, E. (2016). The letter against Derrida’s honorary degree, re-examined.

- Richard Rorty (1931-2007)

- Rorty, R. (1979). Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) 225

- Rejection of the representationalist account of knowledge; mirror of nature.

- Ironism

- Rorty, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. 226

- Rorty, R. (1993). Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and the reification of language. 227

- “Obsession with this image of something deeply hidden” 228

- Rorty, R. (1998). Achieving Our Country. 229

- Rorty, R. (1979). Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) 225

4.10.3 Discussion

- TODO: How much is postmodernism influenced by Marxism and Crticial Theory?

See also:

4.10.4 Criticism

- Criticisms of postmodernism:

- Boghossian, P. (2006). Fear of Knowledge.

- Hicks, S. (2011). Explaining Postmodernism. 230

- Pluckrose, H. (2017). How French “intellectuals” ruined the west: Postmodernism and its impact, explained. Areo Magazine. 231

Boghossian:

Many influential thinkers—Wittgenstein and Rorty included—have suggested that there are powerful considerations in favor of a relativistic view of epistemic judgments, arguments which draw on the alleged existence of alternative epistemic systems and the inevitable norm-circularity of any justification we might offer for our own epistemic systems. Although such arguments may seem initially seductive, they do not ultimately withstand critical scrutiny. Moreover, there are decisive objections to epistemic relatiism. It would seem, then, that we have no option but to think that there are absolute, practice-independent facts about what beliefs it would be most reasonable to have under fixed evidential conditions.

It remains a question of considerable importance—and contemporary interest–whether, given a person’s evidence, the epistemic facts always dictate a unique answer to the question what is to be believed or whether there are cases in which they permit some rational disagreement. So there is a question about the extent of the epistemic objectivism to which we are committed. But it looks as though we have every reason to believe that some version or other of such an objectivist view will be sustainable without fear of paradox. 232

232 Boghossian (2006), p. 109–110.

See also:

4.11 Constructive empiricism

4.11.1 Introduction

Science aims to give us theories that are empirically adequate, but does not justify metaphysical claims about reality.

- Antirealist

4.11.2 History

Bas van Fraassen (b. 1941):

- The Scientific Image (1980)

- van Fraassen’s “Arguments Concerning Scientific Realism” 233

- Unlike positivism/instrumentalism, theories should be taken literally.

- TODO: Some inspiration from Wittgenstein and what else?

- van Fraassen, B. (2002). The Empirical Stance. 234

- van Fraassen, B. (2013). Lecture contrasting naturalism and empiricism.

Otavio Bueno:

- Structural empiricism

Christian Hennig:

- Hennig, C. (2010). Mathematical models and reality: A constructivist perspective. 235

- Hennig, C. (2015). What are the true clusters? 236

See also:

4.11.3 Discussion

- Baker, K. (2020). Video: How to be an empiricist.

4.11.4 Criticism

- Healey criticizes van Fraassen’s CE 237

237 Healey (2007), p. 114–116.

4.12 Structural realism

4.12.1 Introduction

Science has identified real patterns, relationships, and structures (at least within a regime) in nature.

- Realist

- Inverse problem

- Wikipedia: “Inverse problems are some of the most important mathematical problems in science and mathematics because they tell us about parameters that we cannot directly observe.”

4.12.2 History

- Plato’s injunction in the Phaedrus to carve nature at its joints

- Early Wittgenstein: picture theory of language/meaning

- Strucuturalism more generally and structural anthropology: Claude Lévi-Strauss

- Henri Poincaré

- Grover Maxwell coined “structural realism” 238

- Russell 239

- Nozick, R. (2001). Invariances. 240

Plato’s Phaedrus:

Socrates: … [There are] two kinds of things the nature of which it would be quite wonderful to grasp by means of a systematic art.

Phaedrus: Which things?