9 Ethics

Ethics: What should we do? What is good? What is normative?

Meta-ethics: What is goodness? What does it mean to be good? What does it mean to be normative?

Aesthetics: What is beautiful?

What may a man do and not be ashamed of it? He may not do nothing surely, for straightaway he is dubbed Dolittle—aye! christens himself first—and reasonably, for he was first to duck. But let him do something, is he the less a Dolittle? Is it actually something done, or not rather something undone? 1

1 The Journal of Henry David Thoreau, March 5, 1838.

9.1 Virtue ethics

9.1.1 Introduction

- See the discussion of Stoicism.

- Aristotle

- Stoicism

- G.E.M. Anscombe (1919-2001)

- Philippa Foot (1920-2010)

- Rosalind Hursthouse (b. 1943)

9.1.2 Discussion

- TODO

9.1.3 Criticism

- TODO

9.2 Deontological ethics

9.2.1 Introduction

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

- Categorical imperative

- Ernst Mally (1879-1944)

- Deontic logic

- John Rawls (1921-2002)

- A Theory of Justice 2

- The original position

- Veil of ignorance

- Reflective equilibrium

2 Rawls (1999).

Kant:

Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will. 3

3 Kant, I. (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, §1.

9.2.2 Discussion

- Cushman, F. (2013). Action, outcome, and value. 4

- Ayars, A. (2016). Can model-free reinforcement learning explain deontological moral judgments? 5

See also:

9.2.3 Criticism

- TODO

9.3 Consequentialism

9.3.1 Introduction

- Epicurus

- Bentham

- Utilitarianism

- J.S. Mill

- G.E.M. Anscombe (1919-2001)

- Game theory

- Portmore

- Commonsense Consequentialism 6

- Tyler Cowen

- Cowen, T. (2006). The epistemic problem does not refute consequentialism. 7

See also:

9.3.2 Hedonism

- Yang Zhu (440-360 BCE)

- Epicurianism

- De Quincey, T. (1821). Confessions of an English Opium-Eater.

- Hunter S. Thompson

- Christopher Hitchens. (2003). Living proof. Vanity Fair.

- J.J.C. Smart

- Smart, J.J.C. (1956). Extreme and restricted utilitarianism. 8

8 Smart (1956).

9.3.3 Game theory

- Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility theorem

- Brian Skyrms

- Ken Binmore

- D’Arms, J., Batterman, R., & Górny, K. (1998). Game theoretic explanations and the evolution of justice. 9

9 D’Arms, Batterman, & Górny (1998).

9.3.4 Effective altruism

- Peter Singer

- William MacAskill

- Toby Ord

- Derek Parfit

- Janet Radcliffe Richards

9.3.5 Criticism

- Philippa Foot (1920-2010)

- Invented the trolley problem

- Rosalind Hursthouse (b. 1943)

- Coined and further developed the trolley problem

- Bernard Williams (1929-2003)

- Smart, J.J.C. & Williams, B. (1973). Utilitarianism: For and against. 10

- Robert Nozick (1938-2002)

- Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. 11

- The experience machine

- Derek Parfit (1942-2017)

- Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Pearsons. 12

- The repugnant conclusion

9.4 Moral antirealism

9.4.1 Introduction

- The previous three sections are about ethics; the next three are about meta-ethics.

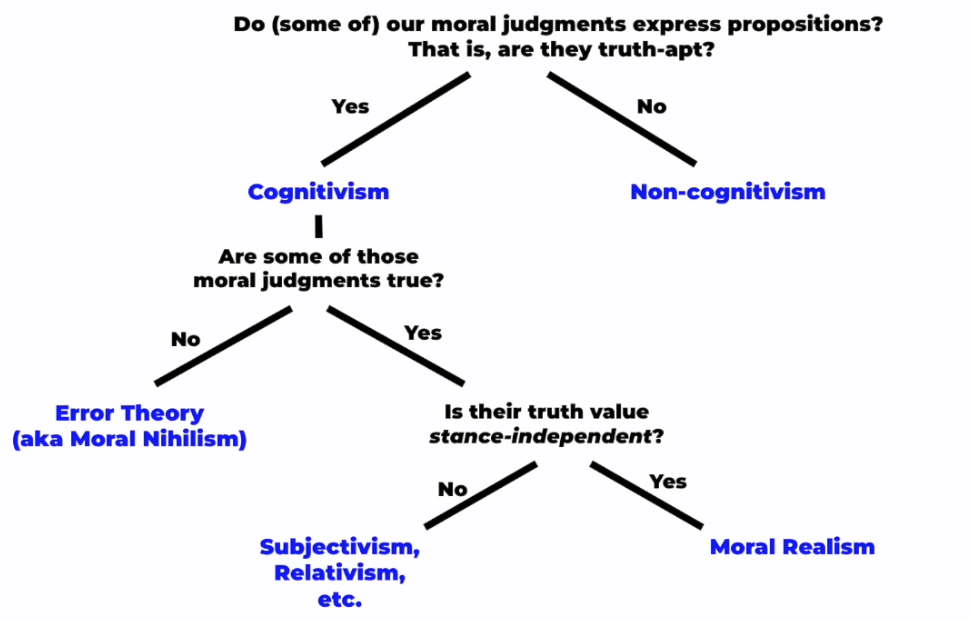

- Cognitivism and non-cognitivism

- Emotivism

- Hume, A.J. Ayer

- Reason is a slave to the passions

- Positivism

- Relativism

- Nihilism

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- J.L. Mackie

- Postmodernism

- Moral antirealism is the disjunction of three theses:

- moral noncognitivism

- moral error theory

- moral non-objectivism 13

13 Joyce, R. (2021). Moral anti-realism, SEP.

Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic:

Listen then, I say justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger. 14

14 Plato, Republic I 338c, Cooper & Hutchinson (1997), p. 983.

Hume:

Morals and criticism are not so properly objects of the understanding as of taste and sentiment. Beauty, whether moral or natural, is felt, more properly than perceived. Or if we reason concerning it, and endeavour to fix its standard, we regard a new fact, to wit, the general taste of mankind, or some such fact, which may be the object of reasoning and enquiry. 15

15 Hume (2007), Section XII, p. 120.

See also:

9.4.2 Is-ought divide

- Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature

- Black, M. (1964). The gap between “is” and “should”. 16

- Schurz, G. (1997). The Is/Ought Problem: An Investigation in Philosophical Logic. 17

- Schurz, G. (2010). Comments on Restall, Russell, and Vranas. 18

- Schurz, G. (2010). Non-trivial versions of Hume’s is-ought thesis. 19

- Pigden, C. (2011). Hume on is and ought.

- Russell, G. (2020). Logic isn’t normative. 20

- Russell, G. (2021). How to prove Hume’s law. 21

- Russell, G. (2023). Barriers to Entailment: Hume’s law & other limits on logical consequence. 22

16 Black (1964).

17 Schurz (1997).

18 Schurz (2010a).

19 Schurz (2010b).

20 G. Russell (2020).

21 G. Russell (2021).

22 G. Russell (2023).

The end of section 3.1.1 from Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature, “Moral distinctions not derived from reason”:

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprized to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, it is necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention would subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason. 23

23 Hume (2009), p. 715-6.

See also:

9.4.3 Noncognitivism

- Noncognitivism is the meta-ethical view that claims about ethics are not propper propositions; they are not truth apt.

- Emotivism; prescriptivism

- Hume, Hare, Carnap, Ayer

9.4.4 Error Theory

- Moral error theory is the meta-ethical view that claims about ethics are truth apt, but they are systematically false.

- J.L. Mackie (1917-1981)

- Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong (1977) 24

- Argument from queerness

- Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong (1977) 24

- Tully, I. (2014). Moral error theory.

- Richard Joyce (b. 1966)

24 Mackie (2007).

9.4.5 Non-objectivism

- Moral relativism, subjectivism

- TODO

9.5 Moral realism

9.5.1 Introduction

- Moral realism is the conjunction of three theses:

- moral cognitivism

- rejection of error theory; some moral judgements are true

- stance independence; some moral judgements are objectively true

- Moral realism can be further divided between moral naturalism and moral non-naturalism, discussed in the next section.

- Plato: Minos

- Objectivity, structure, context, invariance

Plato:

What about someone who believes in beautiful things, but doesn’t believe in the beautiful itself and isn’t able to follow anyone who could lead him to the knowledge of it? Don’t you think he is living in a dream rather than a wakened state? Isn’t this dreaming: whether asleep or awake, to think that a likeness is not a likeness but rather the thing itself that it is like?

I certainly think that someone who does that is dreaming.

But someone who, to take the opposite case, believes in the beautiful itself, can see both it and the things that participate in it and doesn’t believe that the participants are it or that it itself is the participants—he is living in a dream or is he awake?

He’s very much awake. 25

25 Plato, Republic V 476c, Cooper & Hutchinson (1997), p. 1103.

9.5.2 Discussion

- Clifford, W.K. (1877). The ethics of belief. 26

- Victor Kraft (1880-1975)

- The positivist with ethics!

- Rand’s Objectivism

- Railton, P. (1986). Moral realism. 27

- Contectualism

- Björnsson & Finlay (2010) 28

- Game/decision theory, again

- Ethical/moral naturalism

- See below: Moral naturalism

- See the outline on Naturalism.

- Murdoch, Iris. (1999). The Sovereignty of Good.

- Scalon’s Contractualism

- Scanlon, T.M. (1998). What We Owe to Each Other. 29

- Structuralism

9.6 Moral naturalism

9.6.1 Introduction

- Moral naturalism is the conjunction of moral realism and the thesis that moral facts are natural facts.

- Moral naturalism can be further divided into reductive and non-reductive moral naturalism.

- Reductive moral naturalism rejects that the normative cannot be reduced to the descriptive; rejects the is-ought divide

Stephen R. Brown:

Ethical naturalism: Cognitivist ethical theories in which important ethical norms and evaluations are grounded in natural facts. 30

30 Brown (2008).

Moral naturalists:

- Moritz Schlick

- Victor Kraft

- Sam Harris

- Cornell realism

- Richard Boyd, Nicholas Sturgeon, and David Brink

9.6.2 Game theory

- Resnik, M.D. (1987). Choices: An Introduction to Decision Theory. 31

- Binmore, K. (2011). Natural Justice. 32

- Bowling, M., Burch, N., Johanson, M., & Tammelin, O. (2015). Heads-up limit hold’em poker is solved. 33

Resnik:

The best thing to do is to avoid games like the clash of wills and the prisoner’s dilemma in the first place. People who are confronted with such situations quickly learn to take steps to avoid them. We have already mentioned the criminals’ code of silence in connection with the prisoner’s dilemma. Families often adopt rules for taking turns at tasks (dish washing) or pleasures (using the family car) to avoid repeated plays of the clash of wills. Since such rules represent a limited form of morality, we can see the breakdowns in game theory as paving the way for an argument that it is rational to be moral. 34

34 Resnik (1987).

More:

See also:

9.6.3 Evolution of morals

- Robert Axelrod (b. 1943)

- Axelrod, R. (1980). Effective choice in the prisoner’s dilemma. 35

- Axelrod, R. (1980). More effective choice in the prisoner’s dilemma. 36

- Evolution of trust

- de Waal 37

- Patricia Churchland

Churchland:

Our moral behavior, while more complex than the social behavior of other animals, is similar in that it represents our attempt to manage well in the existing social ecology. … from the perspective of neuroscience and brain evolution, the routine rejection of scientific approaches to moral behavior based on Hume’s warning against deriving ought from is seems unfortunate, especially as the warning is limited to deductive inferences. … The truth seems to be that values rooted in the circuitry for caring—for well-being of self, offspring, mates, kin, and others—shape social reasoning about many issues: conflict resolutions, keeping the peace, defense, trade, resource distribution, and many other aspects of social life in all its vast richness. 38

38 Churchland (2011).

9.6.4 Science of morality

- Deontic logic

- Ernst Mally (1879-1944)

- Sam Harris

- The Moral Landscape: How science can determine human values 41

- Video: Sisyphus55 (2020). The Zen Neuroscientist: A guide to Sam Harris.

- Ethical realism and naturalism

- Review: Atran, S. (2011). Sam Harris’s guide to nearly everything.

- Review: Blackford, R. (2011). Sam Harris’ The Moral Landscape.

- Review: Orr, H.A. (2011). The science of right and wrong.

- Harris, S. (2011). A response to critics.

- Harris, S., Blackford, R., & Born, R. (2014). The moral landscape challenge: The winning essay.

- Putnam

- The Collapse of the Fact-value Dichotomy and Other Essays 42

See also:

9.6.5 Nonreductive moral naturalism

- Rea, M.C. (2006). Naturalism and moral realism. 43

- Wedgwood, R. (2007). The Nature of Normativity. 44

- Klocksiem, J. (2019). Against reductive ethical naturalism. 45

9.7 Moral non-naturalism

9.7.1 Introduction

- Ridge, M. (2019). Moral non-naturalism. SEP.

- David Enoch

9.7.2 Naturalistic fallacy

- Naturalistic fallacy

- Introduced by Moore, G.E. (1903). Principia Ethica. 46

- Is/ought divide going back to Hume

- Moore’s open-question argument

- Moore’s moral philosophy

46 Moore (1988).

Bunge:

Still, a gap can be either ditch or abyss. And ditches are not chasms: we may be able to jump over the former though not over the latter. As a matter of fact, we bridge the fact-value gap every time we take action to attain a desirable goal. In other words, action-particularly if well planned-may lead from what is the case to what ought to be the case. In short, action can bridge the logical gap between is and ought, in particular between the real and the rational. This platitude has eluded most if not all value theorists, moral philosophers, and even action theorists—which is witness to their indifference to the real world of action. 47

47 Bunge (2001), p. 193.

See also:

9.7.3 Moral pluralism

- Parekh, B. (2006). Rethinking Multiculturalism: Cultural Diversity and Political Theory. 48

48 Parekh (2006).

9.8 Political philosophy

9.8.1 Introduction

- TODO

9.8.2 Capitalism

- Feudalism

- Mercantilism

- Liberalism

- Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859)

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

- Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973)

- Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992)

- Hayek, F. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. 49

- Libertarianism

- Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State, and Utopia. 50

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Murray Rothbard (1926-1995)

- Neoliberalism

- Neoclassical economics

9.8.3 Marxism

- Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820-1895)

- Dialectical materialism

- The Communist Manifesto (1848)

- The proletariat vs the bourgeoisie

- Das Kapital in three volumes

- The Process of Production of Capital (1867)

- The Process of Circulation of Capital (1885)

- The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole (1894)

- Differential and absolute ground rent

- Engels, F. (1883). Dialectics of Nature.

- October Revolution AKA Bolshevik Revolution (1917)

- Leon Trotsky (1879-1940)

- Marxism-Leninism

- Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924)

- Joseph Stalin (1878-1953)

- Mao Zedong (1893-1976)

- Frankfurt School of Critical Theory

- Max Horkheimer (1895-1973)

- Theodor Adorno (1903-1969)

- Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979)

- Marxism in China

- Mao Zedong (1893-1976)

- Marxism in Britain

- Maurice Cornforth (1909-1980)

- Marxism in the USA

- Michael Hudson (b. 1939)

- Richard D. Wolff (b. 1942)

9.8.3.1 Criticism

Solzhenitsyn:

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart? 51

51 Solzhenitsyn (1974), Part 1, Ch. 4.

Russell in a letter to Wolfgang Paalen (1942):

I think the metaphysics of both Hegel and Marx plain nonsense—Marx’s claim to be ‘science’ is no more justified than Mary Baker Eddy’s. This does not mean that I am opposed to socialism. 52

- von Mises, L. (1920). Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth.

- NY Times. (1982). Susan Sontag provokes debate on communism.

- Berlin, I. (1994). A message to the twenty first century. 53

53 Berlin (1994).

9.9 Philosophy of law

- Philosophy of law

- Legal positivism

- H.L.A. Hart (1907-1992)

9.10 Economics

9.10.1 Introduction

- TODO

9.10.2 Classical economics

- Adam Smith (1723-1790)

- Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834)

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832)

- David Ricardo (1772-1823)

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

9.10.3 Neoclassical economics

- Marginal Revolution

- Léon Walras (1834-1910)

- William Stanley Jevons (1835-1882)

- Carl Menger (1840-1921)

- Alfred Marshall (1842-1924)

- Principles of Economics (1890)

- First to develop the standard supply and demand graph

- John Bates Clark (1847-1938)

- Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923)

- John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946)

- The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936)

- Keynesian economics

- Neoclassical synthesis

9.10.4 Austrian school of economics

- Austrian school of economics

- heterodox

- Carl Menger (1840-1921)

- Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851-1914)

- Friedrich von Wieser (1851-1926)

- Opportunity costs

- Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973)

- Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992)

9.10.5 Macroeconomics

- Cowen, T. & Tabarrok, A. (2013). Modern Priniciples: Macroeconomics. 55

55 Cowen & Tabarrok (2013a).

9.10.6 Microeconomics

- Cowen, T. & Tabarrok, A. (2013). Modern Priniciples: Microeconomics. 56

56 Cowen & Tabarrok (2013b).

9.10.7 Behavioral economics

- Daniel Kahneman (1934-2024)

- Ross, D. (2005). Economic Theory and Cognitive Science: Microexplanation. 57

57 Ross (2005).

9.10.8 Portfolio theory

See my Finance Notes.

9.10.9 Misc

- Amartya Sen (b. 1933)

- Sen, A. (1970). The impossibility of a Paretian Liberal. 58

- Sen, A. (2009). The Idea of Justice. 59

- Bikchandani, S., Riley, J.G., & Hirshleifer, J. (2013). The Analytics of Uncertainty and Information. 60

- Wright’s law

9.11 Free speech

9.11.1 Introduction

- John Milton (1608-1674)

- Milton, J. (1644). Areopagitica.

- Voltaire (1694-1778)

- First Amendment to the United States Constitution (1791)

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

- Pen-friendship with Auguste Comte

- On Liberty (1859)

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841-1935)

- George Orwell (1903-1950)

- Orwell, G. (1946). Why I write.

- Orwell, G. (1946). Politics and the English language.

- Christopher Hitchens (1941-2011)

- Hitchens, C. (2006). Talk on free speech at University of Toronto’s Hart House Debating Club.

- “Don’t take refuge in the false security of concensus.”

- Hitchens, C. (2006). Talk on free speech at University of Toronto’s Hart House Debating Club.

9.11.2 Hate speech

9.11.3 Cancel culture

- NY Times Editorial Board. (2022). America has a free speech problem.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty:

He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion.

9.11.4 Copyright

- Muller, A.C. (2010). Wikipedia and the matter of accountability.

- Suber, P. (2012). Open Access.

- Suber, P. (2016). Knowledge Unbound: Selected Writings on Open Access, 2002–2011.

- Ferguson, K. (2015). Video: Everything is a remix.

- Google Open Source Casebook

9.12 Protests and (non-)violence

- Ahimsa - Indian principle of nonviolence

- Satyagraha - “holding firmly to truth”, coined by Mahatma Gandhi

- Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948)

- Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

- Russell, B. (1943). The future of pacifism. 61

- Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968)

- Osterweil, V. (2014). In defense of looting.

61 B. Russell (1943).

9.13 Feminism

9.13.1 Introduction

- TODO

9.13.2 Women’s suffrage movements (19th and early 20th centuries)

- Seneca Falls Convention (1848)

- John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) and Harriet Taylor Mill (1807-1858)

- The Enfranchisement of Women (1851)

- The Subjection of Women (1869)

- Intersection with the Temperance movement in the US

- American Temperance Society (ATS)

- Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

- Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution (1920)

- Margaret Sanger (1879-1966)

- Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

- Marriage and Morals (1929)

- Bloomsbury Group

- Influenced by Moore, G.E. (1903). Principia Ethica. 62

62 Moore (1988).

9.13.3 Women’s liberation movement (1960s-1980s)

- Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986)

- de Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex.

- Betty Friedan (1921-2006)

- Friedan, B. (1963). The Feminine Mystique.

- Gloria Steinem (b. 1934)

- Steinem, G. (1969). After black power, women’s liberation.

- FDA approves the first birth control pill, Enovid in 1960.

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Thomson, J.J. (1971). A defense of abortion. 63

- Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

- Roe v. Wade (1973)

- Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974)

63 Thomson (1971).

9.13.4 Third wave (1990s-2012)

- Riot grrrl feminist punk subculture

- In 1991, Anita Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her at work.

- Rebecca Walker (b. 1969)

- Walker, R. (1992). Becoming the third wave. (in response to Thomas’s appointment)

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1991)

- Pluralism and staunch disagreement among feminists.

- Feminist sex wars

- Andrea Dworkin (1946-2005)

- Alice Walker (b. 1944)

- Catharine A. MacKinnon (b. 1946)

- Sex-positive feminism

- Camille Paglia (b .1947)

- Naomi Wolf (b. 1962)

- Snyder-Hall, R.C. (2010). Third-wave feminism and the defense of “choice”. 64

- Intersectionality (1989)

- bell hooks (1952-2021)

- Kimberlé Crenshaw (b. 1959)

- Skeptical feminism

- Janet Radcliffe Richards (b. 1944)

- Richards, J.R. (1980). The Sceptical Feminist: A Philosophical Enquiry. 65

- Gender and identity

- Judith Butler (b. 1956)

- Sally Haslanger

- Haslanger, S. (2000). Gender and race: (What) are they? (What) do we want them to be? 68

- Mikkola, M. (2009). Gender concepts and intuitions. 69

9.13.5 Fourth wave (2012-present)

- Use of social media; #MeToo movement

- LGBTQ; Trans rights movement

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)

See also:

9.14 Regret

Thoreau:

Make the most of your regrets; never smother your sorrow, but tend and cherish it till it comes to have a separate and integral interest. To regret deeply is to live afresh. 70

70 The Journal of Henry David Thoreau, November 13, 1839. (What the hell did Thoreau know about regret at age 22?)

- Chand, S. (2016). How to handle regret.

- Marino, G. (2016). What’s the use of regret?

- Pigliucci, M. (2016). What’s the point of regret?

- Danaher, J. (2019). The wisdom of regret and the fallacy of regret minimisation.

- Malesic, J. (2020). Je regrette tout: Does moral growth demand regret?

See also:

9.15 Compassion

- Forgiveness

- Empathy

- Growth mindset

- Compassion in Buddhism

- Compassion in Schopenhauer’s On the Basis of Morality

- Everett L. Worthington Jr.

- Self-compassion

- Serena Chen. (2018). Give yourself a break: The power of self-compassion.

- Wade, N. (2020). Forgive and be free.

- Neff, K. (202X). Self-compassion.

- Limits of compassion

- Ayn Rand (1905-1982)

- Prinz, J. (2011). Against empathy. 71

- Jonathan Haidt (b.1963)

- Anger

- Callard, A. (2020). The philosophy of anger.

71 Prinz (2011).

More:

- Doug Polk interviewing Garrett Adelstein (2021): Being gentle with yourself.

See also:

9.16 Ecology

- Scalability

- Hatcher, B. (2019). Carrying capacity: Our wickedest problem.

- Vegetarianism/veganism

- Peter Singer (b. 1946)

- Michael Huemer (b. 1969)

- Jonathan Safran Foer (b. 1977)

- Herbivorize Predators

- Climate justice

- Hyperobjects

- Timothy Morton (b. 1968)

- Convivialism

- Convivialist International. (2020). The second convivialist manifesto: Towards a post-neoliberal world. 72

72 Convivialist International (2020).

See also:

9.17 Aesthetics

9.17.1 Music theory

- Pythagoras on music

- Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

- Treatise on Harmony (1722)

- Twelve-tone equal temperment: \(2^{1/12} \approx 1.05946\)

- George Russell. (1953). Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization.

- Hemiola: 3/2

9.17.2 Art

- Roman Ingarden (1893-1970)

- Pettit, P. (1983). The possibility of aesthetic realism. 73

- Semiotics

- Roger Scruton (1944-2022)

- Scruton, R. (2018). Why beauty matters. 74

9.17.3 Taste

- Hume, D. (1757). Of the Standard of Taste.

- Goldman, A.H. (1993). Realism about aesthetic properties. 75

- Loeb, D. (2003). Gastronomic realism: A cautionary tale. 76

- Gerkin, R.C. & Wiltschko, A.B. (2022). Digitizing Smell: Using molecular maps to understand odor. Google AI Blog.

9.18 My thoughts

Debating moral realism with Sean Carroll.

AMA question about naturalism and moral realism.

- My question on Sean Carroll’s AMA on reddit

- Repost of the question on his blog

As a fellow physicist (experimenter with ATLAS) also with an interest in philosophy, I’m really impressed by your efforts to push naturalism and engage philosophers. I fully agree with your materialist and reductionist arguments, supporting that we do understand physics within the everyday regime, and this should inform our metaphysics, philosophy of mind, criticism of pseudoscience, etc. I also like that you emphasize emergence as being an important concept in explaining the nested emergent ontologies in chemistry, biology, economics, etc. My question is why you seem to draw a hard line that ethics and morality cannot be analyzed in the same way. You seem to entertain the criticisms that some people say of “scientism”, that there are some things (like ethics) to which the reductive program of science will not be able to explain. This strikes me as totally inconsistent with the thrust of reductionism and naturalism. I think there are reasonable explanations for why ethics emerge as a set of regularities and good strategies anytime you have groups of people. The constraints on ethics seem to be completely determined by the natural world, including the limits of resources, the needs of our physiology, the laws of probability and game theory, etc. There is no fundamental is/ought divide. “Ought” is a higher descriptive term we give to actions that bring out good situations, for which there are objective metrics, such as health and satisfaction. In this regard, I’m sympathetic with some utilitarians and what Sam Harris seems to be describing in the Moral Landscape. Why do you think emergence from natural laws can introduce new concepts like temperature, phase transitions, supply and demand, but not ethics?

Sean’s reply:

Ryan — Essentially, science is about describing the world, not passing judgment on it. Temperature, phase transitions, and supply and demand are all concepts that helps us understand what happens in the world. Morality is just a completely different endeavor. (Of course you can scientifically study how human beings actually behave — including what they judge to be “moral” — but that’s different than studying how they should behave.) Scientific claims can be judged by experiments, moral claims cannot.

See also:

http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2010/05/03/you-cant-derive-ought-from-is/ http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2011/03/16/moral-realism/ http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2013/03/07/science-morality-possible-worlds-scientism-and-ways-of-knowing/ http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2011/01/31/morality-health-and-science/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HCUAR1vH_M

TODO: Drafting a reply.

I know I’m a consequentialist and a moral realist, but those are broad categories.

There’s no unified or received view of the fact/value, descriptive/normative divide since Hume. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t naturalistic philosophers that deny the dichotomy, i.e., would support the idea roughly that there is a scientific way of discussing and determining what is better. Health and nutrition seem like obvious plausible examples, really any reasoned strategy is normative: it tells one what one should do given what is known. In this sense many naturalists are aligned with game theoretic reasoning about what we should do.

Thought experiment on moral naturalism:

- Agree that chess (or poker) has better and worse play

- Add another task to the competition: do laundry while playing, also while trying to sell a product over the phone, or a more typical triatholan: cycle, swim, run, etc. As we add tasks, there doesn’t stop being better and worse overall strategies, albeit complication grows.

- Finally, we ask the meta question of what to do next.

9.19 Annotated bibliography

9.19.1 Putnam, H. (2004). The Collapse of the Fact/Value Dichotomy and Other Essays.

- Putnam (2004)

9.19.1.1 My thoughts

- TODO

9.19.2 Portmore, D. (2011). Commonsense Consequentialism.

- Portmore (2011)

9.19.2.1 My thoughts

- TODO

9.19.3 More articles to do

- TODO

9.20 Links and encyclopedia articles

9.20.1 SEP

- Aristotle’s Ethics - eudaimonia

- Climate justice

- Civic Humanism

- Consequentialism

- Constructivism in Metaethics

- Decision Theory

- Deontic Logic

- Doing vs. Allowing Harm

- Game Theory

- Epictetus (55-135)

- Evolutionary Game Theory

- Existentialism

- Fitting Attitude Theories of Value

- Feminist perspectives on argumentation

- Foot, Philippa (1920-2010)

- Game Theory and Ethics

- Grounds of Moral Status

- Hume, David (1711-1776)

- Hume’s aesthetics

- Hume’s moral philosophy

- Identity politics

- Legal Positivism

- Logics for analyzing games

- Metaethics

- Moore’s Moral Philosophy

- Moral Anti-Realism

- Moral Cognitivism vs. Non-Cognitivism

- Moral Dilemmas

- Morality and Evolutionary Biology

- Moral Motivation

- Moral Naturalism

- Moral Non-Naturalism

- Moral Realism

- Moral Reasoning

- Moral Relativism

- Moral Responsibility

- Moral Sentimentalism

- Moral Skepticism

- Music, Philosophy of

- Natural Law Tradition in Ethics

- Naturalism in Legal Philosophy

- Naturalistic Approaches to Social Construction

- Nature of Law

- Normative Theories of Rational Choice: Expected Utility

- Normativity of Meaning and Content

- Original Position

- Reasons for Action: Justification vs. Explanation

- Repugnant Conclusion, The

- Russell’s Moral Philosophy

- Socialism

- Torture

- Utilitarianism, The History of

- Value Theory

- Virture Ethics

9.20.2 IEP

- Abortion

- Collective Moral Responsibility

- Consequentialism

- Egoism

- Epictetus (55-135)

- Ethics

- Evolutionary Ethics

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Existentialism

- Game Theory

- MacIntyre, Alasdair (b. 1929): The Political Philosophy of

- Metaethics

- Modern morality and ancient ethics

- Moral Egalitarianism

- Moral Epistemology

- Morality and Cognitive Science

- Moral Particularism

- Moral Realism

- Moral Relativism

- Music, Analytic Perspectives in the Philosophy of

- Nihilism

- Non-Cognitivism in Ethics

- Personal Identity and Ethics

- Ross, William David (1877-1971)

- Russell, Bertrand: Ethics

- Stoic Ethics

- Utilitarianism, Act and Rule

- Victor Kraft (1880-1975)

9.20.3 Wikipedia

- Absurdism

- Bentham, Jeremy (1748-1832)

- Big Book thought experiment

- Condorcet’s jury theorem

- Consequentialism

- Emotivism

- Ethical naturalism

- Ethical non-naturalism

- Ethics

- Epictetus (55-135)

- Eudaimonia

- Existentialism

- Existential nihilism

- Fact-value distinction

- Good reasons approach

- Is-ought problem

- Kingmaker scenario

- Legal positivism

- Meta-ethics

- Mill, John Stuart (1806-1873)

- Moral Realism

- Moral Relativism

- Murdoch, Iris (1919-1999)

- Naturalistic fallacy

- Nihilism

- Normative ethics

- Political philosophy

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1712-1778)

- Scalon, Thomas M. (b. 1940): Contractualism

- Social Contract, The

- Trolley problem

- Utilitarianism

- Veil of ignorance

- Victor Kraft (1880-1975)

- Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility theorem

- Yang Zhu (440-360 BCE)

9.20.4 Others

- Consequentialism - RationalWiki.org

- Hume’s law - RationalWiki.org

- “The Kids Are All Right: Have we made our children into moral monsters?” - Daniel Engber

- “Scientism wars: there’s an elephant in the room, and its name is Sam Harris”

- “Why Our Children Don’t Think There Are Moral Facts” - Justin McBrayer

- “Why I think Sam Harris is wrong about morality” - Jonathan Haidt

- The evolution of trust

- The Economy - an online textbook on economics

9.8.4 Socialism

Mark Shields:

54 Shields, M. (2020). The last night of Mark Shields on the PBS News Hour.